Grade Inflation: When A is for Average

At the recent IECA conference in Atlanta, I presented a session on grade inflation with admissions officers from Georgia Tech, Oglethorpe and Emory. We discussed the implications for admissions with so many applicants each year having steadily increasing GPAs. An A average is no longer a distinguishing factor for most applicants, and admissions officers have to work harder to discriminate between students, putting more weight on other achievement factors.

The rise in grades over time reflects a cultural change and a shift in our perception of what grades are supposed to measure. There was a time when Cs and Fs were not uncommon and As were relatively rare. That time has passed. We have shifted to a culture where As and Bs are the norm, Cs occur with decreasing frequency and Fs are rarely, if ever, given.

The shift began at the college level

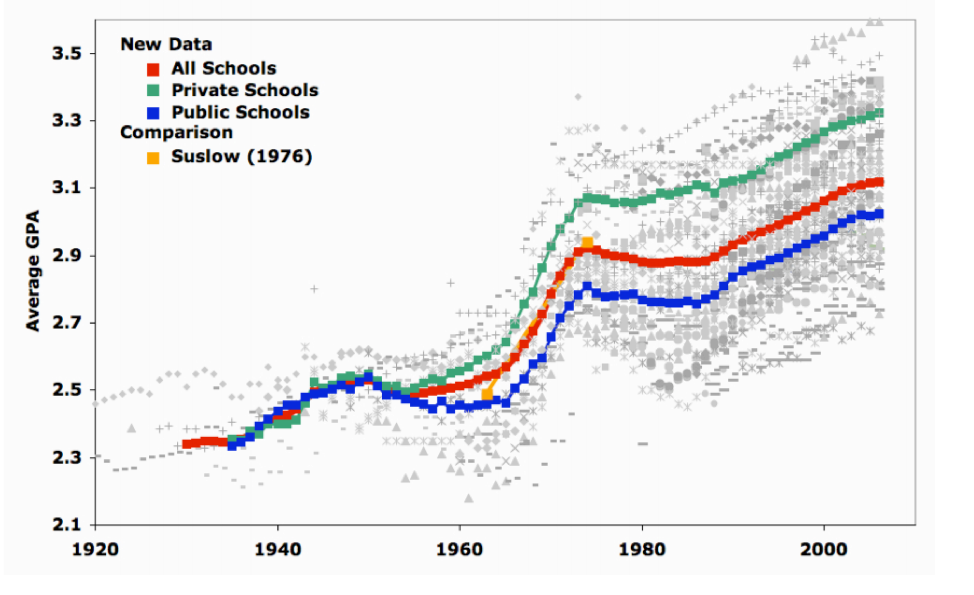

The impetus to shift to higher grades and compress the grading scale first manifested at the college level and then made its way to the high school level. College grades went through a transformation during the latter half of the 20th century. Two academic researchers who conducted a thorough analysis of the shifts in college grading, Stuart Rojstaczer of Duke University and Christopher Healy of Furman University, found that a major shift in grading took place in the 60s and continued for decades following.

Rojstaczer and Healy found that college grading cultures shifted substantially during the Vietnam era where poor GPAs could jeopardize military exemptions. Suddenly the grades being assigned in college classes had consequences well beyond the academic sorting of students. Grades could keep a student from being drafted, and GPAs began to climb.

Sergey Popov and Dan Bernhardt highlighted some of the shifting GPAs in individual colleges and found that more prestigious universities were more likely to inflate student grades.

Popov and Benhardt found that elite colleges like Harvard and Yale were among the worst offenders. In 1950, about 15% of Harvard students received a grade of B+ or better: In 2007, more than half of all Harvard grades were in the A range. At Yale University, approximately 62% of grades were As in the spring of 2012, up from 10.4% in 1963. By 2012 similar institutions were posting highly elevated average GPAs: Brown 3.75; Stanford 3.68, Harvard 3.63, Columbia 3.60, UC Berkeley 3.59. This culture of inflation is highly contagious. Peer schools don't want to see their students at a relative disadvantage in the job market, graduate school market/postgraduate research marketplace. Higher GPAs change student trajectories after college. For these and other reasons, an A grade is now the most common grade given in American colleges and universities, making up 43% of all grades, up from 28% in the 1960s.

Outside factors pressure grades

This phenomenon exemplifies the challenge for grades. In their purest state, grades are unadulterated by outside factors: they simply measure whether or not a student has mastered the material being taught in the class. But inevitably, other factors intrude, and grades are burdened and transformed with the weight of these external forces.

In Georgia, following the implementation of the Hope Scholarship in 1994, which rewarded superior high school GPAs with free or greatly reduced college tuition, high school GPAs of incoming freshmen began to rise without commensurate increases on other measures of academic achievement. The culture at the high school level changed and some Georgia teachers voiced concerns that they were “taking money out of the pockets of families” when they gave a student a C.

In a similar fashion when schools and districts began to be held financially accountable for failing students, some teachers adopted a culture where they would take poor students and “D ‘em up,” rather than fail them and deal with the consequences. Inflating grades allows some schools to meet accountability goals with minimal expenditure. Cultivating weaker grading standards may foster the perception of improvement without the necessary investment to generate actual improvement.

In the era of merit-based financial aid, where higher GPAs lead to reduced tuition as well as better admission outcomes, there is profound pressure for students to receive higher grades. Parents have come into the picture to push grades higher. Parents understand that the grades can have financial consequences for their families, and if they can tip the scales, it can be in their financial interest. Students pressure teachers; parents pressure teachers and administrators; administrators pressure teachers. And GPAs rise. Essentially this is the rise of a “consumer culture” in education as parents and students are flexing their power.

Many teachers now feel differently about what grades are supposed to measure. Many teachers have shifted from norm-referencing, comparing the relative performance of students to establish a distribution of grades, to criterion referencing, where every student can attain an A. Beyond this, many teachers are integrating non-achievement factors such as participation, effort and attitude into their grading rubric. Teachers are also changing their grading behaviors, integrating more bonus points, dropping the lowest test score, curving up, allowing students more chances to resubmit work for regrading, and even allowing students to “negotiate” their final grades. With these changes in place, some students never have to face the disappointment from a low-grade in high school or build the resilience to handle future failures or challenges.

The impact at the high school level

Grades at the high school level have been climbing for decades. Researchers from the Department of Education, the College Board and independent researchers from Fordham and American Universities have confirmed the escalation of high school GPAs. According to the Department of Education, the average High School GPA was a 2.68 in 1990. By 2016, the average GPA, according to the College Board, had climbed to a 3.38. Michael Hurwitz of the College Board and Jason Lee, a researcher at the Institute of Higher Education at UGA, found that the proportion of students with A averages (including A-minus and A-plus) increased from 38.9 percent of the graduating class of 1998 to 47 percent of the graduating class of 2016.

These shifts in grading have enabled us to send more students to college with good GPAs, yet lacking in fundamental skills. Millions of students attend college lacking foundational skills in reading, writing and mathematics and require remedial classes. Students may attain As in AP Calculus and still require remediation for basic math once they shift to the college level. The skill deficits go beyond academics - students reared in this “only-an-A-will-do” environment have often missed the opportunity to experience natural setbacks and build resilience and other emotional coping skills. Inflated grades have distorted the sense of ability and achievement for many students.

How colleges are responding

At the IECA conference, the admissions officers from Emory, Georgia Tech and Oglethorpe discussed the distribution of grades they are seeing from school profiles. At one private high school, 97% of the grades awarded were As and Bs, 2.7% Cs and 0.3% Ds. At another private high school, 75% of the students had weighted cumulative GPAs over 88.5. In this context, a cumulative A average is nothing special.

The admissions officers spoke of their need to explain to parents the difference between different kinds of As. An A is not that distinctive anymore. An unweighted 97 in an advanced class is special, but As alone aren’t enough. It’s a combination of rigor and higher As that distinguish applicants. Some parents who grew up in the grading cultures of old don’t understand how dramatically grading distributions have changed since they were students. Admissions officers have to explain these nuances to families.

Admissions officers also have to view GPAs differently than they used to. A high GPA, by itself, is not enough to validate an applicants ability. They look to other factors to confirm achievement and ability. To validate grades, admissions officers are looking at AP scores, SAT Subject Test scores, SAT and ACT scores, the personal statement, and short answer essays. The grading distributions provided by some high school profiles can also help put student achievement in context.

Conclusion

It’s important for families to understand just how much grades have shifted in America over the last few decades. Grades have succumbed to outside pressures, parental involvement, the competitive atmosphere, and financial forces. With grades significantly inflated, rigor matters more than ever as do other measures of student achievement, including essays, standardized testing, and other factors. Having an A average will put a student slightly above the median for many high schools. The question to ask is: “In what kind of classes?”

It’s no easy task for college admissions offices to allocate scarce seats in an increasingly competitive environment. Grades remain the single best predictor of performance in college, although the predictive power of grades has decreased in this culture of inflation. On the one hand, we know that anything that an admissions office measures is subject to outside influence and “market forces.” If rigor matters to a highly selective college, that college will inevitably “create” students demonstrating higher levels of academic rigor. If grades matter, students will attain higher grades. If grit matters, grittier students will emerge. This would suggest that the competition is only subject to further increase and inflation. But, on the other hand, there are a lot of good colleges out there and there will never be a single factor to determine admissions at any of them. The more we can zoom out and look at the big picture, the more we have a chance to move away from an obsessive and unhealthy focus on any one measure of achievement.

Questions? Need some advice? We're here to help.

.webp)

Take advantage of our practice tests and strategy sessions. They're highly valuable and completely free.